The Seven Features of a Flourishing School

To Create Living Systems, We Must Design the Way Nature Does

As a former high school teacher-turned-school-designer, I’ve had the privilege to work with communities all over the world that are seeking to create the best possible learning environments for children (and working environments for adults).

That perch allows me to notice the global patterns in terms of what schools value, where they struggle, and what they need in order to thrive. And since the pandemic, the primary epiphany I’ve seen educators make is that we must stop stiffly addressing each crisis as it comes up -- and start crafting more adaptive cultures in which we can all work, learn and evolve.

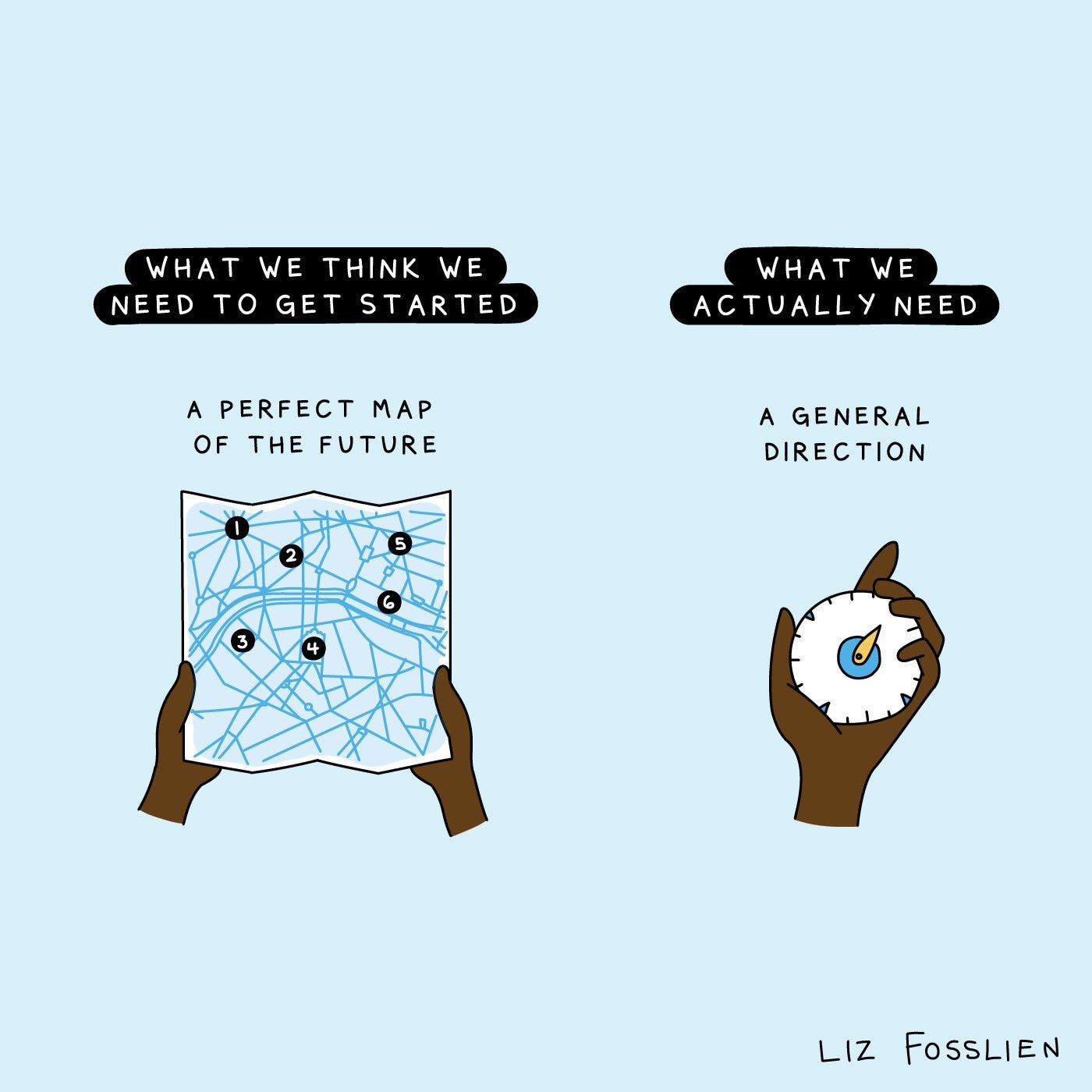

It makes sense that our interest in working this way would be heightened, post-pandemic. But beyond just naming it as an aspiration, what can educators really do, practically and proactively, in order to create schools that are not only healthy and high-functioning, but also resilient and self-regulating?

For the past five years, my colleagues and I have been searching for a more valuable – and viable – answer to that question. Our focus of inquiry has not been how schools function, but how Mother Nature does – and what Her most vibrant, healthy living systems require in order to thrive. And although it may seem counter-intuitive, a central lesson from the natural world is that anything that disturbs a living system is also what helps it self-organize into a new form of order.

Growth, in other words, comes from disequilibrium, not stasis.

So while it’s unrealistic for most of us to just burn the whole thing to the ground and start over, what we can do is critically (and systematically) revisit and renew our priorities and practices, and imagine how we might (re)design them in ways that align with the seven design principles of living systems.

This work is not a quick fix: it’s multi-layered and multi-modal, requiring “urgent patience” on our part, and a willingness to consistently apply a different framework to the way we think about organizational (re)design. Yet what I've seen in schools all over the world is that once you start, it’s also a path that yields lots of quick wins that will help engender a new collective mindset -- one that is more holistic, durable, and, most importantly, effective.

To that end, in the coming weeks I’ll give context to all seven principles of a living system – one at a time – and pair that explanation with a real-world challenge you and your colleagues can complete.

What you’ll discover is a new way to think about how to support healthy learning and growth – a way that’s as old as the Earth itself. And what you’ll gain is a new set of tools to use in helping people change the way they think about teaching, learning and that thing that, up to now, we have always known as “school.”

Try them out, and see what they make clear to you.

Principle One: Identity (Name Your Story)

THE CHALLENGE

Your first challenge is to consider the following: if your school’s culture was staged as a play, would it be a comedy, a tragedy or a drama -- and why? Who would be its main characters? Who would not even warrant a role on stage? Most importantly, to what extent is this the play your community actually wants to be staging? And if not, what is the story you wish you were living out (and in)?

Post a photo or photo essay of your explanation to this challenge at the bottom of this article, and/or share your description on social media with the hashtags #changethestory #7challenges

THE CONTEXT

In life, as with us, everything starts with identity – and with understanding who (and why) we are. And yet at all scales of life – from stem cells to sixth-graders – the process of establishing an individual identity is equal parts “me” and “we.”

“The brain is a social organ, made to be in a relationship,” explains psychiatrist Dan Siegel. “What happens between brains has a great deal to do with what happens within each individual brain . . . [And] the physical architecture of the brain changes according to where we direct our attention and what we practice doing.”

That’s not just a description of how our brains work; it’s also how living systems operate in the natural world -- by existing and creatively organizing within and between a boundary of self. Although this boundary is semipermeable and ensures the system is open to the continuous flow of matter and energy from the environment, the boundary itself is structurally closed.

A cell wall is a good example. It’s the boundary that establishes its system’s identity, distinguishes it from and connects it to its environment, and determines what enters and leaves. But because this meaning of “boundary” is as much about what it lets in as what it keeps out, the end result of this arrangement, according to biologist Andreas Weber, is a notion of self in which “every subject is not sovereign but rather an intersubject -- a self-creating pattern in an unfathomable meshwork of longings, repulsions, and dependencies.”

This epiphany is changing more than just our understanding of the brain. In recent years, scientists in fields ranging from biology to ecology have revised the very metaphors they use to describe their work – from hierarchies to networks – and begun to affirm that partnership – the tendency to associate, establish links, and maintain symbiotic relationships – is a hallmark of life.

The Chilean biologist, philosopher, and neuroscientist Francisco Varela agrees. “Life is a process of creating an identity.” What’s true for the microorganism, in other words, is just as true for the megalopolis.

With that observation in mind, look back at this week’s challenge, and the “play” your school culture acts out every day. What are the primary features of this “self-creating pattern?” To what extent is the story you’re living out the one your community wants to claim as its central identity?

Whatever pattern you observe, the way forward is to become more intentional (and explicit) about the ways people are breathing life into your work together. By design, that work must begin with a candid acknowledgment of what your current co-constructed identity is -- and what you all want it to become. As the Chilean biologist-philosophers Francesco Varela and Humberto Muturana put it, “the world everyone sees is not the world but a world, one which we bring forth with others.”

What, then, is the world you have brought forth in your school -- and what is the one you wish to bring forth more intentionally?

With that answer in mind, we can shift our attention (next week) to Nature’s second design principle -- Information -- and how it travels through a community’s thoughts and actions.

This is how we #changethestory . . .

Great place to begin...to create from. Thank you for the reminder.

This is an extraordinary article! Thank you for this contribution so beautifully articulated. This pulls together so much of what I also believe in as an approach to our times.