What is the Pattern Language of Learning?

and how can we unlock it in order to build a better world?

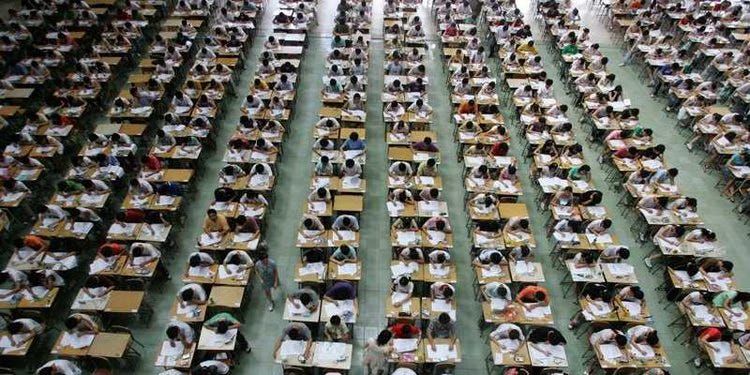

What is the difference between a good school and a bad school -- or, better yet, between an experience that deadens and one that enlivens?

We ask the first question a lot in education, although our most common answer to it -- standardized reading and math scores -- misses the point of the second question entirely.

And yet, if we could answer these questions more clearly, we’d have the recipe we need to reimagine education for a changing world. And after reading Christopher Alexander’s two-volume masterpiece, The Timeless Way of Building and A Pattern Language, I think I see the massive group project that could get us there.

Alexander, who died in 2022, was an architect and design theorist who wanted to understand, as he put it, the “central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building, or a wilderness.” This quality is objective and precise, Alexander explained, but it cannot be named. Yet we all know when we encounter such a space -- whether it’s a courtyard or a farmhouse, a city or a school -- because of the way it makes us feel.

The reason it does so, Alexander contends, is because certain spaces are structured around a set of organizing patterns that place us in sync with the larger rhythms of the natural world. “Every place is given its character by certain patterns of events that keep on happening there,” Alexander writes. “Each building and each town is ultimately made out of these patterns in the space, and out of nothing else; they are the atoms and the molecules from which a building or a town is made. And when a building has this fire, it becomes a part of nature. Like ocean waves, or blades of grass, its parts are governed by the endless play of repetition and variety created in the presence of the fact that all things pass. This is the quality itself.”

What makes Alexander’s books so powerful, however, is the way he translates an expansive philosophy of cosmological harmony into an accessible set of strategies that can guide an actual design project.

“To reach the quality without a name,” Alexander explains, “we must build a living pattern language as a gate. What we want to know is how the structure of the space supports the patterns of events it does, in such a way that if we change the structure of the space, we shall be able to predict what kinds of changes in the patterns of events this change will generate.”

That is the central educational riddle of our time: identifying the irreducible patterns of how people learn best -- spatially, structurally, culturally and pedagogically -- and deconstructing them in such a way that anyone anywhere can use them to transform their own community. And we need such a “pattern language” desperately because, more so than almost any other system in which we find ourselves, education is awash in bad patterns, which as Alexander says, “constantly reduce us, cut us down, reduce our ability to meet new challenges, reduce our capacity to live, and help to make us dead.”

Indeed.

How, then, might we undertake the process of co-constructing a shared pattern language for learning?

How can we render the respective genius of, say, Minerva University, or The Met, or the town of Reggio Emilia, or the science of learning and development, and cross-pollinate all those sources of wisdom into an actionable blueprint for reimagining how we all live and learn?

For Alexander, that process took years -- and yielded 253 patterns in total -- but it was guided by a few clear rules of thumb. “Each pattern is a three-part rule which describes what you have to do to generate the entity which it defines,” he explained. And there are always three essential things we must identify:

What, exactly, is this something?

Why, exactly, is this something helping to make the place alive?

And when, or where, exactly, will this pattern work?

To offer an example, consider pattern #112: ENTRANCE TRANSITION.

“Buildings,” Alexander writes, “and especially houses, with a graceful transition between the street and the inside, are more tranquil than those which open directly off the street.” Consequently, the ENTRANCE TRANSITION pattern instructs us, simply and clearly, to “make a transition space between the street and the front door. Bring the path which connects street and entrance through this transition space, and mark it with a change of light, a change of sound, a change of direction, a change of surface, a change of level, perhaps by gateways which make a change of enclosure, and above all with a change of view.”

That sort of description is both clear enough to be followed by anyone, and open enough to allow for an almost infinite range of expressions.

And that is what we don’t have in education -- and what we need.

Which patterns for learning would YOU suggest, then, knowing that even though their design applications will be infinite, the list of patterns itself must be finite, irreducible, and crystal clear.

I’ll start the bidding with the one that feels most foundational -- and which, not surprisingly, comes to us courtesy of Maria Montessori:

#1: FOLLOW THE CHILD

All people are born with an innate desire to learn -- about themselves, their surroundings, and their place in the social order. Therefore, the most life-affirming learning environments are the ones that, through the arrangement of physical materials, the range of experiential offerings, and/or the variety of community locations, invite young people to make choices about what, where and how to learn that correspond to their own interests -- and occur under the authoritative and caring guidance of adults.

Anyone that has spent time in a healthy Montessori classroom has felt for themselves the power of this particular pattern -- but it exists in a lot of non-Montessori settings as well. That’s because, as Alexander explains, “a pattern is a discovery of a relationship between context, forces, and relationships in space, which holds absolutely. The pattern is an attempt to discover some invariant feature, which distinguishes good places from bad places with respect to some particular system of forces.”

So we have to work to do, together.

We must revisit and reconsider the relationships which really matter in education -- “the ones which are deep, profound, the ones which do the work.”

We must map the patterns that help young people thrive.

And we must co-create a pattern language for the future of learning that reimagines education for a changing world.

Knowing this, what pattern(s) would you nominate for consideration?

Brilliant idea! In some ways, The Third Teacher project took that approach, but it really only scratches the surface of what is a massive undertaking. If you were to expand beyond the school and think about the Pattern Language of a Learning Life, where the city, the world, and the life in and around us was all part of Learning World, it would be sensational! Love it! Go for it!

Love Christopher Alexander's work! Are you familiar with Brandon Hendrickson's substack on Pattern Language? We've had some discussions of Montessori and Pattern Language. https://open.substack.com/pub/losttools?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=onagk